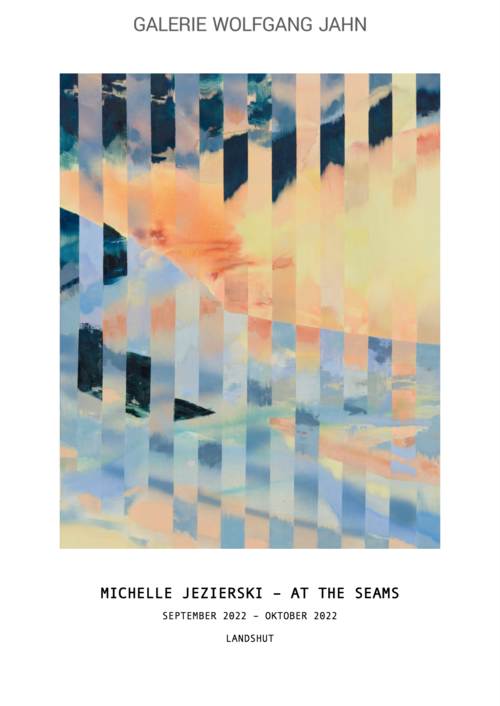

At the Seams - Michelle Jezierski

Images of the Exhibition

Description

With “At the Seams”, Galerie Wolfgang Jahn is showing a personal exhibition of works by Michelle Jezierski, whose work was already presented in 2020 as part of the “Slices” exhibition together with works by Christine Liebich. A catalogue of her artistic oeuvre entitled “Simultaneous Spaces” is being published by DCV-Verlag parallel to the exhibition. The American, born in 1981 in Berlin, where she also lives and works today, studied at Berlin University of the Arts with Tony Cragg and at Cooper Union in New York.

Jezierski’s work is characterised by an unmistakable individual style that is instantly recognisable. Her works, which are largely abstract yet suggest landscapes, are multi-layered deconstructions of familiar reality that lead to a fascinating breaking down of formal and spatial boundaries. In her paintings, for example, one can discern sections and fragments of views of nature, which in their compositional arrangement create a spatially detached, simultaneous sense of self and blur the boundaries between surface and depth through the skilful device of a stripe or grid structure inherent in the picture, overlaying and penetrating individual levels.

In the process, the artist combines and varies the stylistic elements of two art movements that were originally opposed to each other, namely that of “Abstract Expressionism” and “Hard Edge” painting from the 1960s, in a completely individual way. While Abstract Expressionism propagated an unleashed, gestural and free style of painting in which the sensual experience of the painting process came to the fore, Hard Edge painting saw itself as a strictly rational countermovement that relied on a predominantly geometric style and was characterised by a stencil-like, sharply contoured application of paint that clearly distinguished the forms from one another through accurate delineation.

In Jezierski’s paintings, a freely conceived gestural brushstroke is evident in the colour compositions, which in turn suggest landscape elements such as wooded mountains and valleys, blossoms, fields as well as cloud formations and the like on the one hand. At the same time, the artist relies increasingly on a fluid, often transparent-looking application of paint, which is reminiscent of the design principles of watercolour painting with its flowing forms drifting in and out. “Panta rhei”, everything flows, you might say, but it seems to be more than just a design element here. For the flowing movements of the paint application not only convey the impression of dynamism, but can also be read symbolically and transferentially as a formal dissolution of solid structures.

In this detachment from a rigidly fixed physicality, a newfound lightness is revealed, and with it a change in the aggregate state of landscape through painting towards a subtly perceived existence, which also seems to lose its mass through the transparent, often pastel-like colours. This is matched by the fact that the artist deliberately does not give a detailed rendering of a stretch of land that can actually be located topographically, but rather reproduces the essence of a landscape, i.e. creates abstracted visual memories that convey more of a vague overall impression than actually being within reach.

Through the seam-like fragmentation and merging of the pictorial elements into a sequence of mostly clearly delineated stripes, which predominantly follow a vertical, sometimes also a horizontal orientation and at times also occupy different widths as pictorial fields, Jezierski creates a downright complex compositional principle, which consciously relies on an alienation effect, alongside a strictly rhythmically divided structure, which stands in clear contrast to the free painting style. At first the pictures seem irritating, perhaps even disturbing and alienating. As a viewer, you cannot help but think that you are looking through the bars of an oppressive cell from the inside out and only getting a fragmented view of a landscape’s panorama due to the bars impairing your vision. Although the stripes, which are mostly clearly contoured in their appearance, are indeed a visual barrier, they are not in the sense of a solid body but rather define the division of the painting surface as geometrically abstract elements and at the same time demarcated areas in the picture. In Jezierski’s work, this creates a distorted image of reality, which is already abstracted, and at the same time a kind of picture-puzzle again and again.

On closer inspection, you realise that the surfaces of the stripes appear slightly translucent. Sometimes you get the impression that the parts of the background supposedly hidden by them are shimmering through as if through frosted glass in slightly different colours. Then, however, landscape elements on the assumed background move almost abruptly back into the picture surface perceived as the foreground in a different or directly adjacent place, where you would not expect them to be, in particular based on your previous perception. In addition, the juxtaposed sections of nature, which seem like individual snapshots, are slightly offset from one another in their direct connections, another element of irritation that resists the continuity of the depiction in the sense of a seamless visualisation. Georg Baselitz also pursued the latter design element at the end of the 1960s in his “Frakturbilder” (fracture paintings), composed of sections offset from one another in painting, in order to escape the “fatal dependence on reality” using this artistic device.

And then, in Jezierski’s work, you also recognise again and again a free application of paint on the uppermost layer of the picture, which is not restricted by the allocated picture surfaces. A classical division of the pictorial space into a foreground, middle and background therefore no longer exists and can no longer be maintained. The individual levels of the depicted foreground and background alternately spatially and formally permeate each other, becoming a parallel and equal composition and thus finding a simultaneous coexistence on the surface of the picture. Despite the fragmented illusion of spatiality, a dissolution of the spatial boundaries of distance and proximity occurs on the two-dimensional plane in the visual whole.

This is also accompanied by the suggestion of the dissolution of temporality. What is distant and future becomes the present, what is within reach disappears and resists the continuity of chronology. All this happens in Jezierski's work “at the seams” of her picture strips. But the saying “coming apart at the seams” would be more apt. And indeed, the implied reality has become fragile in Jezierski’s work, whereby the Aristotelian dictum that the whole is more than the sum of its parts once again applies here in particular.

Jezierski does not “forcibly” destroy the space that entered art history with the development of the central perspective at the beginning of the 15th century. She gently dissolves it by simultaneously blurring the boundaries of space and time. In this respect, you are also inclined to catch a hint or a glimpse of the concept of the sublime, even of transcendence when looking at her pictures. That moment in which the reference and connection to one’s own physicality evaporates with the last breath.

Dr. Veit Ziegelmaier